2 Mar 2025

The Collapse of Civilization

Although wildfire burn down the suburbs of Los Angeles as never before and are larger than ever, nobody is protesting against climate change anymore on the streets. No Fridays for Future demonstrations, no civic actions to protect the environment, and no climate activists who glue themselves to the streets. As if people have given up. Paralyzed by the events in the USA where the new president denies climate change altogether everyone is in a state of shock. But the problem is still there. And it is bigger than ever.

Although wildfire burn down the suburbs of Los Angeles as never before and are larger than ever, nobody is protesting against climate change anymore on the streets. No Fridays for Future demonstrations, no civic actions to protect the environment, and no climate activists who glue themselves to the streets. As if people have given up. Paralyzed by the events in the USA where the new president denies climate change altogether everyone is in a state of shock. But the problem is still there. And it is bigger than ever.

It is even worse than we used to think. Here is why. Discussions about global warming and climate change are often-dimensional: can we limit global warming to 1, 2 or 3 degrees? And what happens if the world warms by 1, 2 or 3 degrees? [1] Then politicians come together, agree on a certain number, and hope that things change for the better, while in reality nothing happens. As if all we need is to tweak a single number in one dimension. Global warming is just one aspect of a much bigger set of problems. The first problem is that small policy changes are not enough if the root problem is the economic system of modern society which demands constant growth. The second problem is the fundamental “limits to growth” problem described by Dennis Meadows et al 50 years ago [2].

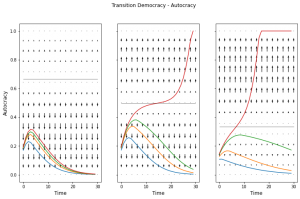

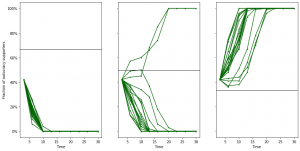

Dennis Meadows et al have shown that exponential growth based on non-renewable resources in a finite world eventually leads to a collapse of the whole system. While resources decline, population and pollution go up, until they reach a peak and the system starts to collapse. The wildfires we haven seen in recent years in increasing frequency and intensity are only first signs of a changing climate. While the rise in global temperatures caused by burning of fossil fuel remains certainly one of the biggest problems, there are other problems caused by our non-sustainable lifestyle, including plastic pollution, overfishing, overpopulation, deforestation, ocean acidification, waste disposal, etc. The problem is unlimited growth is not possible in a limited system, and yet our economic system is based on it. The 50 year old predictions are unfortunately still accurate [3]. They say on the business as usual path that we are on resources will plunge, pollution will increase and eventually civilization as we know it will collapse. You can experiment with the world3 model here.

How close are we to a total collapse of human civilization? Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens argue it is not far ahead. They predict everything can and will collapse soon, simply because infinite growth is not possible in a finite world where resources are limited. Soon means in the next one or two decades, but certainly in this century. Their book “Everything Can Collapse: A Manual for our Times” [4] mentions two models that predict and describe the collapse of civilization: the classic World3 model from “The Limits to Growth” and the “HANDY” model which describes human and nature dynamics by simple Lotka-Volterra equations which are so common in ecology. Both models are already older but still relevant. Somehow people have forgotten what they predict if we do business as usual. Climate change is only a part of it.

I believe the 2nd Trump government is a sign that the collapse of civilization and the subsequent looting have already started. The 43th U.S. president George W. Bush admitted the country is addicted to oil. The 45th & 47th U.S. president is a sympton of a society addicted to fossil fuels which has reached peak oil and started to realize that resources are depleted but is unwilling or unable to change and has severe withdrawal symptoms. The models predict that it will go downhill from here until civilization collapses- – which has happened before on a smaller scale [5].

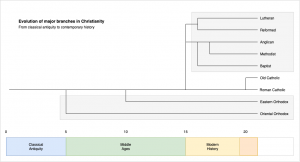

Where did it all start? Now that we are reaching “limits to growth” worldwide some of us are wondering where the imperative for growth which is so destructive and devastating for nature comes from. Stock markets, corporations and their relentless desire for constant growth have their roots in European colonialism and imperalism. Joint-stock companies like the East India Company, the Virginia Company, the British South Africa Company or the South Sea Company helped to build the British empire as Philip J. Stern describes in his book [6].

This joint-stock venture colonialism laid the foundation for modern corporations and stock markets. The British East India Company, French Mississippi Company, Dutch East India Company, and German Brandenburg African Company were the first European stock corporations. Investment in joint-stock companies allowed investors including the royal family itself to gain large profits at high risks, similar to investors in whaling ventures which shared risks and profits. Modern venture capital was born, and venture colonialism turned over time into venture capitalism [7].

In this sense colonialism enabled imperialism and led to capitalism. Capitalism won against communism, because communism robs personal motivation and stifles innovation, but as we begin to see now, it has drawbacks too. Unchecked capitalism will apparently lead to the collapse of civilization and to a total demise of Earth’s ecosystem – the only habitable place for humans we know.

[1] The Uninhabitable Earth – Life After Warming, David Wallace-Wells, Crown Publishing Group, 2019

[2] Limits to Growth, Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and William W. Behrens III, Potomac Associates – Universe Books, 1972

[3] Limits and Beyond: 50 years on from The Limits to Growth, what did we learn and what’s next? Ugo Bardi and Carlos Alvarez Pereira, Exapt Press, 2022

[4] How Everything Can Collapse: A Manual for our Times, Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens, Polity Books, 2020

[5] Goliath’s Curse – The History and Future of Societal Collapse, Luke Kemp, Knopf Publishing Group, 2025

[6] Empire, Incorporated: The Corporations That Built British Colonialism, Philip J. Stern, Harvard University Press, 2023

[7] VC: An American History, Tom Nicholas, Harvard University Press, 2019

Unsplash photos: vehicle escaping wildfire by Marcus Kauffman and road to wildfire smoke plume by Malachi Brooks